On Wednesday 21st November 2012, I attended a lively debate on "Museums in the Information Age: Evolution or Extinction?", held at the Science Museum, London, as part of the Leicester Exchanges series. The event has been reported in several reviews, including a detailed analysis by Liz Lightfoot.

The panel included Ian Blatchford (Director, Science Museum Group), Carole Souter CBE (Chief Executive, Heritage Lottery Fund) and Ross Parry (School of Museums Studies, University of Leicester), and was chaired by Prof Sir Robert Burgess, Vice-Chancellor of Leicester University

The discussion was wide ranging and stimulating. Much of it related to the ability of digitisation to improve access, and whether increased page views were linked to increased or decreased footfall. Ian Blatchford believed strongly in digitisation and summed it up as “It breaks up the cosy club. Something still lurks in the museum world which I call the grand connoisseurial view. There was a time when only a select number of people knew where to find the archives and so they had access to material for their PhDs. Now ordinary people can access amazing archives and that is just as important as what actually happens in museums."

Despite the wide ranging nature of the discussion, I felt it largely missed the important opportunity that digitisation provides - namely the opportunity to allow the (digital) objects we care for to be reused in all manner of ways far beyond our own imaginations. Just because we curate and care for the objects, it doesn't give us the exclusive right to their interpretation.

The real future is in web services - communication between electronic devices over the world wide web. The British Geological Survey already uses Web Services to make a variety of map, dictionary and lexicon type data freely available. A number of museums are starting to provide similar access to their collections, frequently using APIs (Application Programming Interface). Key examples include the V&A, London; the Brooklyn Museum, New York and the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. Web services will provide anyone anywhere with the means to devise their own exhibitions using selected items from the world's major collections. What better way is there of demonstrating to our funders that our collections really have an impact?

Tuesday, 22 January 2013

Monday, 21 January 2013

The Yorkshire Museum, and John Phillips

“Educated in no college I have professed geology in three universities and

in each

have found this branch of

science firmly supported by scholars, philosophers, and divines."

There are many famous names associated with the history of

the Yorkshire Museum (the museum itself was founded to house the collection of

fossil bones from Kirkdale cave, famously studied by William Buckland), but one

that is not widely known outside geological circles is that of John Phillips.

Phillips was the nephew of William “Strata” Smith and came

to Yorkshire with him in 1819 where he helped Smith as he travelled the

countryside seeking work as a surveyor. Phillips showed a keen aptitude for

arranging the collections of local museums, and in 1826 took up the post of

Keeper of The Yorkshire Museum, which he held for many years.

A list of his accomplishments throughout his career is long,

and it has already been commented that “it is amazing to think that he was able

to accomplish anything other than write during the whole of his lifetime”[1]!

In particular, to mention but a few things, he:

· Worked out the structure of the rocks found on the coast and in the dales of Yorkshire, and published these in two books in 1829 and 1836.

· Was a founder member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and was instrumental in organising it’s inaugural meeting in York in 1831

· Introduced the term Mesozoic – the “middle age” of life on earth

· Helped in the foundation and arrangement of the University Museum of Oxford in 1859

· Carried out work for the (then quite recently formed) British Geological Survey, studying the Palaeozoic fossils of Devon, Cornwall and West Somerset.

· Taught geology in three universities, in London, Oxford and Dublin, all with no formal education beyond the age of 15!

In particular, to mention but a few things, he:

· Worked out the structure of the rocks found on the coast and in the dales of Yorkshire, and published these in two books in 1829 and 1836.

· Was a founder member of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and was instrumental in organising it’s inaugural meeting in York in 1831

· Introduced the term Mesozoic – the “middle age” of life on earth

· Helped in the foundation and arrangement of the University Museum of Oxford in 1859

· Carried out work for the (then quite recently formed) British Geological Survey, studying the Palaeozoic fossils of Devon, Cornwall and West Somerset.

· Taught geology in three universities, in London, Oxford and Dublin, all with no formal education beyond the age of 15!

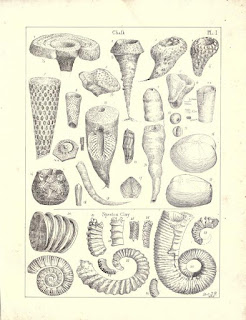

The JISC 3d Fossil Types Online

team has just returned from a week long

visit to the museum, and we were lucky enough to be able to work with a number

of the original specimens that Phillips collected nearly 200 years ago and

subsequently illustrated in his book, Illustrations of the Geology of Yorkshire.

One such specimen shown below is Hamites

phillipsi. The work being done on the Fossil Types Online project will help

to increase the visibility of specimens like these to a worldwide audience.

Simon Harris

[1]

Sheppard, T. John Phillips, Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society 1933, v.22; p153-187. doi: 10.1144/pygs.22.3.153

Not just labels - potted histories?

The

JISC GB/3D Type Fossils Online project is not solely about fossils – we are

also photographing any historical labels which are associated with the

specimen, like those that you see in the example below

The labels affixed to the back of this specimen carry a “potted history” of the fossil, and tell us a lot of things, such as:

·

The

original date, collector and location

·

The

specimen has been renumbered at least twice – we might find these old numbers

referred to in old accession registers or catalogues

·

The

specimen has been recognised as the type of it's species, and assigned a new

name, in this case Vetacapsula hemingwayi

We

already store much of this information on our publicly accessible database, PalaeoSaurus

so why bother to photograph it again? Well, some of the reasons include:

·

As

a safeguard against mistakes made when transcribing the data – although we are

as careful as possible, mistakes may have been made in the past

·

Being

able to examine a sample of the handwriting of a particular known collector or

curator can prove extremely valuable in identifying other unknown specimens

·

To

protect against loss – old labels may not be on archival paper, or written with

archival ink, or they may simply fall off the specimen and become lost

We

hope that this has provided an insight into another part of our process. In

case you were wondering, Vetacapsula hemingwayi is the name given to the

egg-case of a prehistoric shark. Their appearance, coupled with the fact that

they were frequently found associated with fossil plants in the Coal Measures

rocks, meant that for many years it was believed that they were some kind of

plant fossil.

Simon Harris

Stunning 3D fossil videos - reach out and catch them!

The "soft launch" of the GB3D Type fossils online project web portal is planned to coincide with the Lyme Regis fossil festival in May 2013, but before then we have lots of stunning 3D digital fossil models that we would like to share with everyone. Chris Wardle at the British Geological Survey (BGS) has taken some of our more interesting 3D models and turned them into YouTube videos. He has done two versions - one where the fossils are shown as rotating fossils in 2D, and one where they are shown as rotating fossils in 3D anaglyphs. You will need red - blue glasses to see these properly - but some of the fossils are stunning. You feel as if you can reach out and catch them!

Link to 3D anaglyph rotating fossil video

Link to 2D rotating fossil video

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)